“The Death of an Athlete”

by Fr. Denis Farkasfalvy

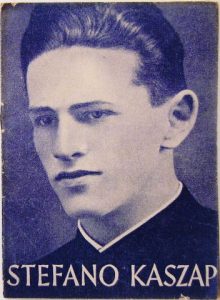

István Kaszap lived just a little more than nineteen years, eight of them as student of a Cistercian School in Székesfehérvár, Hungary and just a little more than one as a novice in the Society of Jesus. His novitiate was interrupted by a poorly diagnosed illness. Once he returned to the novitiate, but then he had to be sent away for an indefinite period of time. Canon Law did not allow another dispensation for absence from the House of the Novitiate. But he circumvented Canon Law: he joined both the Jesuits and the Cistercians, the two orders he at various times considered to enter, in heaven.

As a boy István was very ordinary. His name, the Hungarian form of “Stephen,” is one of the most common in that country. He grew up in Székesfehérvár, a city where King St. Stephen had reigned and was buried a thousand years ago. Not only was the Cistercian School named after St. Stephen, but also the city’s Museum of Arts, its best hotels, the theater, squares and streets – along with a dozen other things. When István was addressed by his nickname “Pista” (pronounced “Pishta”) at least a dozen other boys of his school could have thought someone was talking to them.

His school had been in the hands of the Cistercians since 1813. With a long history, the school cultivated the memory of many of its “famous alumni” – writers, poets, politicians, architects, scientists, actors – but István Kaszap was not like any of them. He became a “hero” of modern sainthood in an unexpected and still unexplained way, especially when, a few years after his death, a biography based mostly on excerpts of his diary was published. A number of religious people discovered that a young man of “ordinary sainthood” lived and died among them. Up to this day fresh flowers cover his tomb.

The documents of Kaszap’s life – his diary and the testimonials of his contemporaries – suggest a three-fold division of his life.

Part One: An Ordinary, Happy Childhood

In his first fifteen years “Pista” Kaszap was a normal, good-natured, though a bit stubborn, and (only in hindsight) somewhat peculiar child. He had two older brothers and two younger sisters. The family was poor. After World War I, Mr. Kaszap, an assistant postmaster, had a hard time supporting such a big family. But in those years, the Cistercians in Hungary were still well enough endowed; the tuition at their school was nominal, and for the three Kaszap boys even that was reduced.

Yet Pista began school reluctantly. In fact he hated the idea of going to school altogether. On the first day of school in first grade, he resisted so much that his mother threatened to call the police! Yet, for the first few years his grades were good. At home, he was trained to be an obedient child. However, as the curriculum grew harder, his playfulness took over: he spent his afternoons and evenings playing with his little sisters and with the neighborhood kids instead of studying. He was not lacking ambition. At an early age he made the decision – of which most everybody was unaware – to become a priest. His motivation is not quite clear. It is known that he cherished the memory of an uncle who was a priest and died at an early age and that he kept a picture of this uncle at his desk. In any case, his performance in school did not correspond to his lofty goal. In Fifth Form he began to collect C’s, some of which became D’s in Sixth Form.

At that time, the Cistercian Order was starting a program for candidates to the priesthood. Pista thought of applying (he would have become a classmate of Fr. Anselm Nagy, the first abbot of Our Lady of Dallas) but his Form Master told him: “with the grades you make nobody can give you a letter of recommendation…” So, Pista did not even apply. This experience must have been a shock for him. For the first time he was told that he was not good enough for his goal in life. And yet, such a blow proved to be the moment of grace, for by it he was awakened to a true vocation, one that demanded of him a change of heart and of life.

Part Two: Crisis and Conversion

In Fall of Sixth Form, his grades bottomed out: in Math and Latin he was close to failure and he actually did fail Art History. Not a single A appears on his report card, not even in conduct (for someone failing, the school’s regulations did not allow an A in conduct). But in the second semester, a sudden change appeared in his grades which even his teachers did not realize until only months later. By the end of Sixth Form, no F or D was left on his report card. His personal life also took a turn a significant turn. He joined, and soon took leadership roles in, the newly organized Boy Scout troop of his school. In the early mornings, he began to serve mass and receive daily communion.

The following summer is recorded in minute details in his diary. He set up a plan of using his time for daily exercises in Latin, French and Math, and for reading books he had previously skipped. With his savings he bought a bicycle and went on tours to “discover the world.” He began collecting material for his Boy Scout patrol: stories, skits, jokes and songs. He even started to study Spanish and Italian on his own.

In the fall of Seventh Form, a new activity was announced by his gym teacher – gymnastics. István proved himself to be a natural talent and by the end of the school year he collected ten medals at various competitions (four bronze, three silver and three gold). One week before his seventeenth birthday he earned first at a national championship and became the top gymnast in the region.

Meanwhile his grades continued to improve. By the end of Seventh Form he had only two B’s; all the rest of his grades were A’s. In Eighth Form, he performed even better, graduating from the Cistercian school in Székesfehérvár with straight A’s.

During this last year of success an extraordinary personality began to shine through his everyday life. “Shining” may not be the right word, since the distinctions he obtained by hard work and a deepening spiritual life seemed to embarrass him and make him even more unassuming and modest. His Form Master – a real teaser, but a man of great insights – even declared: “Pista, you are suffering of micromania!” The rest of the class couldn’t forget such a statement since their Form Master usually chastised them on account of their “megalomania” – that is, for thinking too much of themselves.

Some time over the last three months of his senior year, Pista made the decision to enter the Jesuit Order. Until that time he had only heard of Jesuits, having never met one personally. But one day he happened to meet a Jesuit holding a retreat in another school of the city. After two encounters with this Jesuit, and after attending his own school’s retreat, led by a Carmelite priest, Pista had reached a decision. He would announce three months before his high school graduation: “Mother, I will be a Jesuit!” His mother, however, was worried: “We were always poor, and now you want to remain poor for the rest of your life!” At it happened, that was exactly what Pista wanted: “In the past we had all we needed, why would I want any more in the future?” Later, when asked why he preferred the Jesuits to other orders, he gave an unusual answer: “I wanted to live a life of true poverty.”

Part Three: The Death and Birth of an Athlete

Pista entered the novitiate with unreserved trust and enthusiasm. His peers liked and admired him. But their esteem did not change his unassuming attitude. In fact, it seems he was reluctant to heed the requests of his novice mates to perform the impressive exercises for which he had received his fame as a gymnast. But when one of his peers, lacking athletic talent, asked him to teach him to perform simple gymnastic exercises, Pista behaved like a mature educator without ever showing off.

At this point in his life, Pista’s diary reveals his deepening insight into the spiritual needs of the world around him. A growing awareness came over him about the all-pervasive presence of temptation and sin in so many young lives and the redeeming power of the cross. A spirituality of prayer, expiation and sacrifice began to unfold in his mind, as he experienced an ever more intense chain of physical suffering.

In retrospect, he probably had a bacterial infection centered on his tonsils. Unfortunately, the doctors did not make the right diagnosis and in 1935 there were no antibiotics. Pista developed a number of painful blisters on various parts of his body. He was hospitalized in the spring and lost a lot of weight; but after some primitive treatments he seemed to get better. With special dispensation from the Superior General of the Jesuits, he was able to return to the novitiate. Leaning on a cane, the once powerfully built athlete must have looked like a shadow of himself. Yet he was happy to be back on course, following his vocation. Sadly, in early fall the signs of infection were back. This time the doctors discovered the problem; they removed his tonsils, but at the wrong time, and, possibly, in the wrong way. His weakened body rapidly deteriorated further. At the advice of the doctors, he was sent home to rest with the promise that, after he recovered, he could start overhis novitiate. This was probably his last and biggest sacrifice: he had been formally dismissed from the haven he had found, the Order he learned to know and love as his own. He copied out the text of the profession of religious vows, intending to recite it privately, and went home. There his condition changed from bad to worse as he began to suffer from septic shock. His throat swelled up such that he could no longer swallow. In panic, his parents took him to the local hospital. In a few days, the condition of his throat worsened to the point that he could no longer breathe. The doctors, working pro bono on account of the family’s poverty, performed an emergency tracheotomy; and from then on he was unable to speak. The notes he wrote on a pad preserve his last thoughts and dialogues with those around him.

On the night of December 16, 1935, he signaled to a nurse that he needed a priest for the last rites. He knew he was dying. At his insistent notes, the nurse – a young religious sister – went out into the night to fetch the chaplain (there was no telephone) and a doctor. It took her about fifteen minutes to get help. When she returned, Pista lay unconscious. On the notepad next to him was his last message: “Mom and Dad, do not cry – this is my heavenly birthday!” In ten minutes he was dead on earth, born in heaven; the death of an athlete turned into the birth of a saint.

It is hard to tell how the veneration of Pista Kaszap began. I know how it began with me. In 1940, I was four years old and close to dying of pneumonia (again, there were no antibiotics). My mother clipped a “relic” – a piece from the last Jesuit habit of Pista – to the ice-cold packing around my chest, one of the prescriptions of the doctor. “Pista Kaszap helped,” my mother said, as I recovered. So at such an early time, just five years after Pista’s death, ordinary people in our town were praying for this young man’s intercession.

By 1942, the crowds visiting his grave grew so big, that his body was transferred to a new tomb. Meanwhile, a large amount of evidence was collected about the impact of this saintly boy’s example, turning people to God and obtaining by his intercession miraculous cures. Already as a child I met respectable and reliable people who told me about miracles they had witnessed, and which were obtained from God through the intercession of Pista Kaszap. The local bishop spent several years collecting testimonials and examining every known facet of his life as well as the facts reported about the power of his prayers. Shortly after the Second World War this diocesan investigation was formally closed and the local bishop allowed the veneration of his tomb, as that of a saintly man. The tile “servant of God” was conferred on Pista and written on his tomb. The records were sent to Rome in 1946 for obtaining official canonization.

Then came the cold war. The Communist authorities forbade every instance of religious “propaganda.” The case of Pista Kaszap must have bothered them in a particular way, because both a novel and a play were produced in order to mock the “artificially created saint” and product of “Jesuit conspiracy.” Such efforts had little effect on religious people, for in large numbers they kept going to his tomb. During those a most moving poem was written about Pista by a poet who found his faith through him.

As a ten-year-old I read a biography of István Kaszap and was deeply impressed. His example made me decide to become a priest. I never changed my decision, but I carried out his first intention: I became a Cistercian.

However, only decades later, and after twenty some years of teaching Sixth Formers and Seventh Formers, did I understand Pista’s story. Now I know much better the plight of bright boys failing in school and wanting to come close to God but not finding the way. I have seen many conversions of boys his age; they were of diverse nature, impact and success. In the mirror of “ordinary teenage life,” as I see it today, Pista Kaszap, the young Cistercian alumnus, appears to me as a true saint, one for our times and for our needs. Recently I began to ask him – just by prayerful conversation – to take under his care the Cistercian alumni of our school in Dallas, and also the ones who graduate from Jesuit College Preparatory School. We all need, greatly, the three things Pista achieved in the course of just three short years:

- Conversion: a change of heart and life.

- Realization of the power of prayer and sacrifice for combating sin.

- Acceptance of God’s call with eagerness and joy.

Today Pista would be seventy-seven years old. For me, he is nineteen, freshly graduated from the Cistercian in my heart. I am still impressed by him, but today I look at him as if he was one of our alumni: a young friend who graduated last year.

For a biography written by Jenő Bóday, SJ, click here.