Below is a collection of short excerpts from a few of the writings that shape the ethos and spirituality of the Cistercian Order. The websites of Cistopedia, Medieval Institute of Western Michigan University, Analecta Cisterciensia, and Cistercian Publications are helpful aids for someone seeking to learn more about Cistercian history and spirituality.

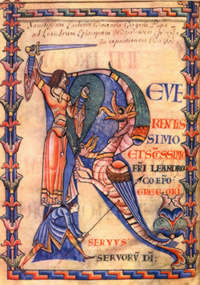

Exordium Cistercii

This simple early narrative of the foundation of Cîteaux, called at that time “the New Monastery,” is notably understated: amid the precise notifications of bishops and transitions of abbots, we can discern the zeal with which our holy Founders strove to secure the possibility of their peaceful following of the monastic ideal of poverty, of wholehearted fulfillment of the vows. It is no small task to organize and systematically nourish the life of grace without quashing it: perhaps the great insight of our Founders was the centrality of love, codified in the Carta Caritatis. The unity they strove to implement even at the most detailed levels was unity in the bond of love.

Click to read: Exordium Cistercii

Carta Caritatis

“That there may be no discord in our daily actions, but that we may all live together in the bond of charity under one rule and in the practice of the same usages.” This little constitution of sorts attests the early Cistercian attempt to achieve the unity of what we now call a “religious order”. The unity is first of all spiritual, grounded in the love which springs from Cîteaux to nourish her offspring to maturity. But the practical is not overlooked: books should be the same, practices should be similar, so that the tranquil peace of love can reign and grow in our monks, precisely through the simple practices of the monastic life. Love, if it be true, does not blind and stupefy us, but kindles in the heart a fire that enlightens our every practice and unites us closer to each other.

Click to read: Carta Caritatis

Cassian Conference I, I-IV

St. Benedict himself recommends the reading of Cassian, and with good reason. This Conference represents the first step in what would be Cassian’s great translation of Eastern and Egyptian monastic wisdom into a Western, Latin setting. In these very first paragraphs of the first of his Conferences, Cassian shows us abbot Moses explaining how the monastic life is an art or discipline, not just a vague spiritual quest. Like farming, like business, it has both a final goal, and something else, a practical target, as it were, at which we aim in order to reach the goal. Abbot Moses proposes, then, that the target which animates our communal effort is not the ambition to construct the largest, most beautiful, most prestigious monastery, but purity of heart. We seek the kingdom of God by striving in all we do for purity of heart, in the hope that God will grant us this as by the order of seasons he renders fruitful the discipline of the farmer.

Click to read: John Cassian – Conferences I I-IV

The Confessions of St. Augustine (354-430) is one of the most influential spiritual writings of all time.

Augustine

Confessions X, 69-70

Among the countless roles St. Augustine plays in the life of the Church, one is his position as an early institutor of monastic life around himself as bishop. In this text, the conclusion of the tenth book of his Confessions, and the last paragraphs describing his conversion, Augustine gives us a profound vision of the connection between the grace of conversion and our life in communion. Leaving despair behind by contemplation of the Incarnation of the Son of God, Augustine admits that he thought of living the life of a hermit, only to realize next that “Christ died for all.” Our very conversion impels us to union with those who likewise long to quench their thirst at the fountain of our Savior for all eternity: a union in the Church, in the Eucharist, lived also in our monastery as each individual is called to share in a “communal vocation”.

Click to read: Augustine – Confessions X 69-70

Tract VII on First John, 8-9

“Love, and do what you will.” Augustine proposes love as the universal lens through which to understand all actions, from the Father’s handing over of his only Son, to our own lives. Likewise, in the monastery, we strive to conform our own union in love with the unity of the Father and the Son. We do not merely seek to live justly with each other, rendering each his due, or just balancing our various ‘legitimate needs and desires’; we first of all seek love, in prayer, in work, in the whole life of the monastery, assured that that love revealed on the Cross will guide us.

Click to read: Augustine – Tract VII 8-9 on First John

Rule of St. Benedict, Chapter 64

St. Benedict links the discretion required of the abbot to the love and mercy required of him. By discretion he “must so arrange everything that the strong have something to yearn for and the weak nothing to flee,” that is, do all he can to ensure a unity among the brothers that allows all to grow as they can. The monastery is a school of service, a place of prayer and work, of patience and spiritual progress; but it is none of these without being a school of love, rooted in the heart of the abbot, the “principal”, but also in all the “students”.

Click to read: Rule of St. Benedict, Chapter 64

Bernard

On the Steps of Humility and Pride III

In this short, early work, St. Bernard comments on the seventh chapter of St. Benedict’s Rule, the “steps of humility.” Bernard proposes a sort of monastic philosophy, a three-step way of truth that begins from the humility perfected in the practice of the Rule. Monks too are “lovers of the Truth,” but the Truth we seek is none other than Christ, who became man and died for our sins, the Truth that frees our hearts and makes them grow, uniting us to our brothers and to the Truth itself. Thus, humility is not a “lack of self-esteem,” but the very path we take in our search for God, the path Christ made of himself, saying, “I am the Way, the Truth, and the Life.”

Click to read: Bernard of Clairvaux – On the Steps of Humility and Pride III

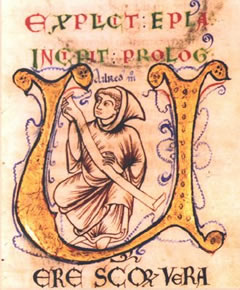

William of St.-Thierry

On the Nature and Dignity of Love, 24-27

William of St.-Thierry, a Benedictine monk and dear friend of St. Bernard who eventually became a Cistercian, offers us here an image of the monastic life as a “school of charity,” in which the whole order of life is conceived as a “melody composed according to the rules not of music but of love”, and the debates and courses occur at the level of experience, not ratiocination. The brothers’ obedience and the abbot’s self-sacrificing service of authority ensure that peace which is necessary to this “melody” composed of the aspirations of the heart shared even in silence.

Click to read: On the Nature and Dignity of Love, 24-27

Isaac of Stella

Sermon 31, 17-21

In this passage from one of his Lenten sermons, Bl. Isaac of Stella, an early Cistercian abbot, makes a striking comparison between the devil’s eagerness to find cause for damnation in us and our own eagerness—mostly lacking—to find cause for salvation in our brothers. If we had charity, which “bears all things,” we could truly follow Christ’s law of compassion, rather than participate in the devil’s petty warfare. And we can have it, for Christ himself grants us this love.

Click to read: Isaac of Stella – Sermon 31 17-21

Life of Aelred of Rievaulx, 29

The Life of Aelred written by his friend and doctor Walter Daniel offers this stirring homage to how well St. Aelred fulfilled the role of the Abbot set out by St. Benedict: during Aelred’s abbacy, Rievaulx in England was truly the “mother of mercy,” prospering from its abbot’s concern for the weak. He guided his flock to live in every moment of their monastic life the beatitude “Blessed are the peacemakers.”

Click to read: Aelred of Rievaulx – Life of Aelred 29

Baldwin of Ford

Treatise XV, On Life in Common

Another early Cistercian abbot and archbishop of Canterbury, Baldwin of Ford, portrays the “common life,” or life lived in community, as a participation in the communion of grace. The monk does not merely strive for his own spiritual progress amid brothers to whom he is united only by the weakness of their shared human nature. Rather, he lives the grace he has received fundamentally as a grace of communion, a grace that impels him to a unity beyond his weaknesses and even his merits: grace lived within the context of the union of the brothers, of the Church, of the Communion of Saints, and ultimately of the Holy Trinity. And thus Baldwin prays, “Keep me among those who keep the unity of the spirit in the bond of peace.”

Click to read: Baldwin – Treatise XV